Gifted, resourceful, and unwaveringly focused, Nancy Pearcey embodies the spirit of a generation of Christian thinkers that has more than held its own in a secularist and even “agnostic” age.

Called “the modern-day successor to Francis Schaeffer,” she has quietly risen in stature through three decades of Christian worldview advocacy covering a range of ideological fronts. Nancy Pearcey’s emergence as a thinker and Christian apologist has been such that The Economist magazine recently dubbed her “America’s pre-eminent evangelical Protestant female intellectual.”

Pearcey’s lucid, accessible style and her atypical (for a scholar) readiness to contend in such non-academic realms as journalism, talk radio, the blogosphere, and the popular press have placed her in elite company.

Like Ross Douthat of The New York Times and Michael Horton of radio’s White Horse Inn—both eloquent, savvy commentators who have thrived in popular, mainstream media—Pearcey reaches a public not reached by most scholars and academicians.

Douthat is the Times’ conservative Op-Ed columnist—a young, Harvard-educated Christian with a Chestertonian bent—and Horton, in his “day job,” is a university professor of Christian theology and apologetics. But like Pearcey, they have defied easy categorization and have earned hearings and influence within the public at large.

This new breed points up, by their very existence, the public’s appetite for Christian intellectual engagement, in an age when the prevailing postmodernist culture would have many believe that Christianity is facing marginalization.

Not that Douthat and Horton are closest to Pearcey in subject matter. Her nearer comparisons there would be such figures as Os Guinness, James Sire, Michael Wittmer, Phillip E. Johnson, Michael Behe, J.P. Moreland, and the like, as well as Schaeffer protégées Udo Middelmann and Ranald Macaulay (both of them sons-in-law of Schaeffer).

For a Q&A with Nancy Pearcey about her coverage in the New Yorker‘s controversial profile of Michele Bachmann, go here. For Something Solid’s strongly opinionated commentary on the so-called “Dominionism controversy” that has attached to Bachmann, Schaeffer, and Pearcey, visit this page.

Even so, Pearcey (herself a past student of Schaeffer’s at his famed L’Abri sanctuary in Switzerland) is unique. Her latest book, Saving Leonardo: A Call to Resist the Secular Assault on Mind, Morals, and Meaning, marks her as a thinker with a common touch, someone with a finger on the pulse of today’s truth-seeking, Christianity-sympathetic masses.

Marvin Olasky, editor-in-chief of World magazine, calls Pearcey “super-intelligent and persevering in her cultural mission.” American Spectator, in its review of Pearcey’s latest book, observed that “the breadth of learning that she brings to bear is remarkable.” Dan Peterson, author of that review, asserted that Pearcey “lays bare the secular presuppositions that have increasingly come to underlie literature, the dramatic arts, the plastic arts, and music.”

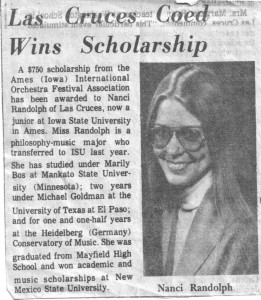

Her professional career breaks out roughly into three phases: from 1977 to 1990 she published articles and analyzed Christian worldview themes for the Bible Science Newsletter. In 1991 she became founding editor of the daily radio program Breakpoint, where she would serve through the decade of the 1990s as the head of a team of writers producing broadcast commentaries. Under her intellectual leadership, Breakpoint steadily gained following until it reached a weekly audience numbering an estimated 5 million. In the past 12 years, Pearcey has authored books (most notably Total Truth: Liberating Christianity from its Cultural Captivity and the aforementioned Saving Leonardo) and held university academic posts. She has appeared on National Public Radio and C-Span and has lectured at the Heritage Foundation. In June she relocated, with her husband Richard, from the Washington, D.C., area—their home for more than a decade—to Minneapolis, Minn., where the couple fill new teaching positions at Rivendell Sanctuary.

A recent interview with Pearcey found her focused on exposing the roots of what she calls “stealth secularism.” And on countering any notions that any worldview can be values-neutral.

“People say, ‘You’re a Christian—so you’re biased.’” Pearcey said. “That is the assumption—that if you are coming from a theological perspective, you’re biased. And so people say, ‘We don’t have to pay attention to you. You don’t belong on the public square. The secular view is the unbiased view. The objective view.’

“That’s what we run into in much of academia, in politics, in business—it is the main strategy used to marginalize Christians,” she added. “The strategy has been to maintain that the secular view is objective. Well, the secular view is not objective. The secular worldview is just as much a biased perspective as any other philosophy. But that [presumed neutrality] has been used to slip secular views into the classroom, and into the public arena, without acknowledging that they are just as much intellectual convictions as a theological conviction is, and that they carry their own biases.”

Though she derives this orientation from Schaeffer, Pearcey has advanced her own philosophical and theological positions to such a degree that her work stands apart as something more than merely derivative.

“If you’re looking for a simple redux of Schaeffer’s work, look elsewhere.” So says Bill Wichterman of Pearcey’s work. Wichterman, a former special assistant to President George W. Bush and former policy adviser to Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, has known Nancy Pearcey and her writer-editor husband Richard for a number of years. Wichterman believes that Pearcey “advances well beyond Schaeffer, both in the maturity of her thought and in her original work with source documents.”

Wichterman, who has been an innovative thinker in his own right, pioneered the idea that “politics is downstream from culture.” This concept—the idea that politics does not steer culture, but that the reverse is true—undergirds Pearcey’s thesis that Christians need to be more than critics of culture, they need to be active creators of culture. It’s the idea that, in culture, “the good drives out the bad” and that a society’s worldview prefigures its outlook and ideas.

Wichterman knew the Pearceys from their mutual involvement with Faith & Law, a D.C.-based nonprofit that “helps congressional staff better understand the implications of the Christian worldview for their calling to the public square.”

Another individual who became acquainted with the Pearceys through Faith & Law was Stovall Witte, a former congressional chief of staff. He now serves as chief operating officer of the Coastal Educational Foundation, a nonprofit that manages private resources for Coastal Carolina University.

Calling Nancy “one of the nicest and smartest people [he] has ever met,” Witte described the author as “the leading philosopher of worldview thinking,” and added that her writings “just changed my life.”

After a career in the Army as an infantry officer, Witte came to Washington to work on Capitol Hill. “I’d lived my life believing in absolutes,” he said. “And when I got to Washington, D.C., it was a huge change for me. And very frustrating. I didn’t understand how these people thought. I wondered, who would lie to you and not think there was anything wrong with that?”

It wasn’t, Witte said, that the people he’d known in his youth and in the military didn’t do wrong. Of course they sometimes did wrong. It wasn’t that they didn’t commit any sins. But the difference, Witte said, was that those individuals he knew earlier in life had never really questioned the idea that there really is such a thing as right and wrong, such a thing as sin.

What he learned in Washington is that there are people today who do not question their own or other people’s behaviors, for the simple reason that “those are really just personal preferences.”

Witte didn’t need Pearcey’s help to believe in absolutes. He already accepted absolutes. What he got from Pearcey is an understanding of how culture can foster belief systems that reject absolutes. “She helped me to understand, through her books, how these other people thought,” he said. “[Her writings have] shifted the way I look at things and at the way I interact with people and go about my business. It has helped me ask the right questions of how God wants me to live my life. I am incredibly impressed with Nancy not just as person, but as an intellect.”

Added Witte: “Rick [Nancy’s husband, Richard Pearcey] is a great guy. Rick is more political than Nancy is. They make a really good team. He is a great editor—he was with Human Events for a long time.”

Identifying herself as a child of a particular time and place—Nancy has made it known that she is the child of second-generation American parents of Swedish descent, Lutheran in upbringing, Midwestern and middle-class in background—Pearcey has tracked a career that is of distinctively American “Boomer” vintage. She progressed from an agnostic, counterculture teen to a searching, uncertain early-20s college kid adventuresome enough to hitchhike from Las Cruces to Albuquerque, N.M., there to spend a summer at a Christian “crash pad” cohabited by a coterie of “ex-hippie ‘Jesus freaks.’” Stubbornly independent-minded, bookish, artsy, musically talented, and driven enough to make not one but two lengthy forays to L’Abri, Pearcey fit the image of the typical searcher-for-meaning of her generation.

It was in her second visit to L’Abri, in the fall of 1972, that she met Richard, but they would not form a relationship for some years.

Born in Germany, Richard had returned to Budingen in 1971 to spend some time before returning to the United States to finish his college education. He knew about Francis Schaeffer, and decided he would “go down to L’Abri and see if Schaeffer put his money where his mouth is.” He’d heard others trying to “tell you how to live” only to find that their advice didn’t work. He would see if Schaeffer was different.

“I hitchhiked down to Switzerland, and it was during that time that I met Nancy,” Richard said. “I was not out to get a girlfriend. I was interested in thinking things through, as to whether Christianity was true or not.”

Richard and Nancy were on friendly terms in L’Abri, but there was no serious romance. He was taken with her—smitten might be a better word—but he knew he needed to find answers about life before pursuing a mate.

“So when she left [to return to America], my prayer was, well, God, if you are there, [and] if this is the one for me, then please put her on ice for about five years and thaw her out after that time.”

Four years later they reconnected and Richard staged a whirlwind courtship—a month or two long, by his recollection—and they were wedded.

Meanwhile, Richard and Nancy both had concluded that Schaeffer had, in fact, “put his money where his mouth was.”

“Seeing the ministry around him, seeing how he treated people, how they dealt with questions—and, overall, [recognizing] the ethos that it was just ‘normal life’ to discuss things. In other words, to question faith. To question Christianity. To scrutinize things. This convinced me,” Richard said.

As Richard would write in 2005: “Schaeffer had worked through agnosticism and concluded that the Judeo-Christian worldview is objectively true—that is, that the system of thought and life set forth in the Old and New Testaments alone answers the basic philosophic questions of life in a way that is rationally consistent, historically verifiable, and existentially livable.”

The Pearceys have gone on to create a body of work uniquely their own. Richard, a journalist, created the online news-and-commentary site pearceyreport.com, where both he and Nancy regularly post their own views and provide a venue for others’.

One of Richard’s recent projects was serving as primary editor of David Limbaugh’s bestselling book Persecution.

Limbaugh said that the Pearceys work well together.

“Rick is a great force in his own right for worldview thought and conservative thinking,” he said. “Their work on their website is very good, too. Nancy is scholarly. A great thinker and a great writer. She grasps worldview issues as much or more than anybody writing on them today. I consider her the modern-day successor to Francis Schaeffer. As a student of his, and as someone carrying on his work, she brings to the discussion a knowledge of theology, as well as a knowledge of politics and social issues. I think she is the whole package.”

Limbaugh said Nancy Pearcey approaches worldview in a comprehensive way, from a Christian perspective.

“In her most recent work [Saving Leonardo] she has given us some perspective on our history and our cultural development,” he said.

Describing secularism as a worldview “competitive with the Christian worldview,” Limbaugh commended Pearcey as someone who “has her finger on the pulse of secularism and its insidious consequences.”

But the Saving Leonardo author is more than a diagnostician, at least in Limbaugh’s view. He said that Pearcey’s gift is her ability to trace the roots of many contemporary worldviews to their secularist origins. In doing so, Pearcey gives us a road map.

“She helps us understand the full context of the [societal and political] issues we are facing, in all their multidimensional aspects,” Limbaugh said. “We can see that [a particular contemporary issue] is not just an economics issue, or not just a domestic policy issue or a foreign policy issue. By tracing the origins of problems back to their sources, we can better understand them and—if necessary—better oppose them. We can tackle them—take them on—and counter their detrimental effect on society.”

In that respect, Pearcey is filling a void that would otherwise exist in the Christian community’s response to secularist influences. Pearcey’s efforts are helping “to ensure that the social issues and religious issues are not overshadowed by issues of domestic policies and foreign policy,” Limbaugh said.

Byron Borger, a bookseller (Hearts and Minds Books) in Dallastown, Pa., and someone who knows Pearcey from personal acquaintance, describes the author as scrupulous and industrious.

Byron and his wife Beth became acquainted with Pearcey when she was at work with her first book, The Soul of Science. The author asked for some recommendations on source materials. The Borgers obliged, and they have scouted a few new titles for Pearcey to read for more recent projects as well. “We do know the high caliber of her [Pearcey’s] scholarship. And we know how much work she does on the books she writes,” Byron said. “If you just look into the endnotes for Saving Leonardo, you’ll see that she has covered the territory.”

Borger is right about Saving, which is assiduously annotated. “She has read deeply—it’s a wide range of thoughtful stuff that she’s doing,” he said.

A couple of years ago, Borger was with Pearcey when she visited a local Christian college in his area to give a talk from her 2004 effort, Total Truth. He recalls being impressed with an idea she shared with him. “I was driving her around afterwards, and she told me how interested she was in how the ‘genealogy of ideas’ work—how ideas shape culture. An idea she developed in Total Truth. And she said, ‘I think I want to do it [explore that] in the arts.’”

Borger remembers thinking that the idea sounded inspired. “Artists often see things the rest of culture hasn’t see. They get there first—artists popularize ideas. I said, ‘Nancy, if you could do that, that would be great.’” With a laugh, he added, “She would have done it anyway, of course, but I was pleased just to be on hand to hear about it and give it a thumbs up.”

The project, of course, became Saving Leonardo.

“She’s just so articulate,” said Borger. “A great communicator. Gives good speeches. Very compelling. If someone is interested in contemporary culture—if someone wants to know why we got the way we are today—this [book] is the way. It’s fun. It’s about the arts and movies and stuff. If you want to study culture and get a diagnosis of what is wrong in our society, but in a fun way, this is it.”

Asked what has been the biggest surprise to her, as regards the reception she has received for Saving Leonardo, Pearcey said it has been the interest that has arisen from non-Christian quarters.

“Maybe a fourth of the [media] interviews have come from non-Christian sources,” Pearcey said. “The fact that it has gone outside the Christian ghetto—that’s been a surprise, because in many ways my books in the past have had primarily a Christian audience in mind. But many non-Christian radio hosts have picked it up and said, ‘This is an interesting book in its own right.’ For example, I had an interview on a radio program in New York City with a host who, from his website, did not appear to be a professing Christian, and whose focus was on the day-to-day details of politics. But it turned out that before going into radio, he had been a novelist, so he was very interested in talking about the integration of ideas with the arts.”

Pearcey noticed, in the process of creating the book, that its focus on the arts proved appealing to young people. As a teacher in an association of home schoolers (the Pearceys home school their youngest son), Nancy used the book, in manuscript form, as part of her teaching curriculum.

“I taught it to high schoolers,” she said. “This book has been winnowed through the minds of teenagers. They were the best editors I ever had. Anything they didn’t understand, I went back to the drawing board and edited and rewrote and changed so that they would understand it.”

The book’s “arts element” addresses the whole person, Pearcey believes.

“I have ‘cognitive kids’ and ‘creative kids.’ The students who like apologetics and defending their faith and… [she laughs] arguing… are what I call the ‘cognitive’ kids. But then you’ve got your ‘creative kids’—the ones who love the arts and literature and want to read and paint pictures. Both types find something in this book. They find a way to integrate the two. The cognitive students are fascinated to learn that there actually are ideas behind the various art movements. Many of them have told me, ‘I never even liked art before I took this class.’ And the creative students discover that there are depths to art that even they had not realized, that artists are conveying their deepest convictions about life.”

Maybe it’s the evangelical in her—the societally engaged, cause-minded, family-values side of her—that accounts for her devotion to homeschooling. But whatever the source, Pearcey surely ranks as one of the most accomplished and credentialed academics ever to commit so wholeheartedly to that humble educational milieu that is the home school.

Her homeschooling peers say they find inspiration in her enthusiasm.

“It’s really a treat to be with her,” said Maria Dunn, a fellow parent who filled a teaching role in the same neighborhood homeschooling cooperative (W.H.E.A.T.—We Home Educate And Train) where Pearcey taught in the past school year. “Our relationship has come a long way. She has taught a couple of my sons, and other kids in the community, for a while now, and when they’ve come into town, she’s gone to lunch with them and wanted to know what is going on in their lives. She has a gift for reaching young people. Definitely. They like learning from her.”

Describing Pearcey as “scholarly, intelligent, and personable,” Dunn added that her friend is “very down to earth.”

Dunn’s home (in the D.C. area) has been the site of much of the schooling, at least prior to the Pearceys’ move to Bloomington, and has even served as a think tank for some of Pearcey’s brainstorming.

“Sometimes, after we’d finish [with their respective teaching duties], we’d go for a walk while my husband was teaching an English class,” Dunn said. “And Nancy might be working on an article for Human Events or some other publication. And she’d say, ‘Here is what I’m thinking about.’ She would ask for our input. Sometimes we’d have a great interchange of ideas.”

The same goes for home school strategizing. Said Dunn: “Come January or February, we’d start thinking about the next school year. And when that happens, she’s always right there. She gets excited about the ideas and the plans.”

Dunn described Pearcey as a “really positive” person. “Of all my good friends, I can think of only about one or two whom I have never seen down, and that’s true of her,” Dunn said. “I have never seen her down. She handles everything that comes her way with… something. I’m sure it is her Christ-centeredness.”

Pearcey is passionate about being able to influence the culture and reach people for Christ, Dunn said. “She has stood firm on that—on making sure that that comes through in the books she writes.”

In the opening passages of Saving Leonardo, Pearcey tells the story of how her son Michael came to love the work of John R. Erickson, the bestselling author of the “Hank the Cowdog” series of books and audio tapes for children. In an unrelated development, Erickson, a Texas cowboy-turned-author, gave an interview in 2006 to World magazine for a profile article that caught the eye of Pearcey, who immediately began reading – and quite understandably, because her household was a “Hank” household. Not such a rare thing, that: sales of Erickson’s books and tapes are approaching the 8 million mark. In the article, Erickson spoke of the influences of his Christianity upon his work. As he later described it, he had never before been regarded as a “Christian writer.”

“During the interview, I made reference to a book that helped shape my opinions about my mission as an author,” Erickson said recently.

That book was How Now Shall We Live, by Pearcey and her co-author Charles Colson.

And so Pearcey, who is reading along in World‘s profile of John R. Erickson, finds herself reading about herself.

Pearcey immediately wrote to Erickson, identifying her son as a “Hank” fan and herself as an admirer of Erickson’s work, and thanking Erickson for his sentiments.

Erickson takes it from there: “I wrote her back and gave my assessment of How Now Shall We Live: a tremendous piece of scholarship and a source of inspiration that led me to other champions of the faith, including Francis Schaeffer and C.S. Lewis. She mentioned another book she had written, Total Truth, and sent me an autographed copy. It wasn’t easy reading, but I could hardly put it down. Several years later, I went through the same process with her next book, Saving Leonardo, which I had the pleasure of reading in manuscript.”

Erickson found in Saving Leonardo a theme that continues to resonate with him.

“In all her writings, Nancy has pounded home her message,” he said. “Christians have been sleeping through one of the most profound intellectual revolutions of all time. Clinging to ‘faith’ and ‘values,’ we have forfeited the right to define simple, everyday Reality. We still own our churches, but they’re half-empty, and we’ve been expelled from the places that really count: universities, government, and all the instruments of popular culture.”

In 2008, Erickson brought out a volume of his own, Story Craft, in which shared his own “reflections on faith, culture, and writing” and in which he paid tribute to those contemporary writers and thinkers who have influenced him: individuals such as Pearcey and Gene Edward Veith, among others. (For a profile of Erickson himself, go here.)

Pearcey cuts through the distractions of contemporary culture to isolate life’s true essentials, Erickson says.

“We’ve been mugged by Starbucks versions of Marx, Darwin, Nietzsche, and Freud, and that is shameful enough,” he said. ” The crowning disgrace is that we had a better intellectual and spiritual program to start with, and we stood around and watched while bullies tore it to pieces and left it in the gutter.

“That’s a powerful message for Christians. It’s also Bad News for smirking journalists, art salon nihilists, and the Postmodern intellectuals who like to flip lighted matches in the basement of Western Civilization.”

Pearcey, for her own part, says that these are critical times for Christians.

“Evangelical Christians are really struggling with how to re-enter the public arena, and how to craft a message that works in the public domain,” she said. “It goes back to the late 19th century and the architects of the modern age: Darwin, Marx, Freud. The trouble is that Christians of the time really did not have the intellectual resources to respond to these major challenges. To a large extent they turned inward, retreated from the public domain, and circled the wagons. The idea was to stay within your churches, schools, summer camps, and so on. This was the Fundamentalist era of the early 20th century. Many conservative Christians thought the way to respond to culture, as it became secular, was to turn their back on it—to pull away and form a separate subculture. The literature of the time actually promoted what was called ‘separatism’ as the correct stance toward mainstream culture.

“Of course, it didn’t work. If you don’t have a TV, your kid will go to the neighbor’s house and watch their TV. You cannot hermetically seal off the outside world. It seeps in. But more importantly, people began to say, ‘This is really not what scripture calls us to do.’ Scripture calls us to go out into the world, to bring God’s truth into the world and apply it, and to be agents of God’s cultural redemption, as well as agents of spiritual redemption.

[Article continues below video window.]

“So in the 1940s and ’50s, you started to see a movement—Francis Schaeffer was important here, and Carl F.H. Henry—saying that Christians need to engage with the modern world. As a result, evangelicals today have become convinced that it is important to engage with the modern world, but it must be admitted that they often don’t know how to do it. They don’t have the language, they don’t have the thought forms—they’ve lost a century of practice in knowing how to do it. Saving Leonardo equips them by asking, ‘Okay, what are the dominant secular worldviews out there?’ Let’s get them under our belt, let’s learn how to respond to them, let’s analyze their weaknesses, so that you can get out there and start engaging with people who think this way. And then let’s learn how to make the case, in the public square, that Christianity has better answers to the major questions that all the philosophies, and all the worldviews out there, seek to answer: What is ultimate reality? What is human nature? What is the basis for morality? You will be equipped to line up the various worldviews side by side and see which one gives the best answers. You will learn how to make the case that Christianity does in fact answer the questions better than any other worldview or philosophy.”

Pearcey said she personally wrestled with most of the “-ism’s” she analyzes in Saving Leonardo. And that, she said, is why she is as passionate as she is about questions of worldview. It is because they have been such a big part of her own life.

“You run into people in the Christian world who say, ‘Just have faith. Don’t think about it,’” she said. “But I think it is a matter of loving your neighbor. Loving your neighbor enough to be willing to find answers to their questions. Even if they are not your questions. [It’s a matter of] respecting people.”

Finding answers to questions—one’s own and others’ as well—is something Nancy Pearcey has been doing all her life. And so it is appropriate that, in summing up, she identified this as a basic need that is shared by all.

“We are made in God’s image,” she said. “Everyone has a mind. Everyone needs to know the ‘why.’ Someone might not be an intellectual per se. But that person was made in God’s image—that person has a rational mind and needs to know why things make sense. We still need answers to our questions.”

Jesse Mullins is a career journalist and former editor-in-chief (Art Today magazine, American Cowboy magazine) who lives in Abilene, Texas. For more on Mullins, click here.

For this writer’s book review of Saving Leonardo that was published by christianpost.com, go here.

For the Pearceys’ website (pearceyreport.com), go here.

For our just-posted (Aug. 30) Q&A with Nancy Pearcey in the aftermath of the controversy raised by the New Yorker‘s profile of Michele Bachmann, a profile that discussed Pearcey, see this page.

For a hard-hitting opinion piece on the entire New Yorker – Bachmann – Schaeffer – Pearcey – so-called-Dominionism-controversy, go here.