What does it take to paint a patriotic/Christian image that, when displayed and discussed in a YouTube.com video, draws 3 million hits and 2,500 comments? Well, it takes faith, apparently.

If any additional evidence were necessary to establish the reality that the political winds in America have shifted markedly, even troublingly, in the span of just a few short years, that evidence could well be derived from the experiences of a fine artist by the name of Jon McNaughton.

It seems that the talented McNaughton has learned firsthand just how far this nation has swung from its moorings. His strongest-selling image, a sublimely patriotic historical tableau entitled One Nation Under God, has been at once a smashing success and (unexpectedly) a lightning rod for backlash. [Scroll down for more of article.]

McNaughton at the easel, painting One Nation Under God

If McNaughton’s story is any indication, some of our most cherished national beliefs are now regarded by millions as distortions and falsifications.

As for the mixed bag of being successful and sniped-at — more in a moment. For now, a different, though related, thought. As I sit lounging on our living room sectional, laptop atop my lap, tapping out the opening lines of this article, we have the television playing and the set is tuned to a History Channel program. It’s the first of six episodes of a 12-hour extravaganza called America: The Story of Us. (If you want to jump ahead to the promised coverage of McNaughton and avoid this disgression on a television show, click here.) Why say anything about our evening’s entertainment fare? Because it suddenly strikes me that this televised exercise in historical revisionism bears some relation to the biases and prejudices faced by our Mr. McNaughton.

Having done my research on McNaughton, and thus being aware of the scorn heaped on him from some quarters, I made sure I caught the opening episode of this series, because a question was already forming in my mind. Would the makers of this series even so much as mention Christianity? After all, America was founded by Christians. I didn’t need Jon McNaughton to tell me that. But McNaughton’s brush with hostile, vocal nonbelievers made me wonder if filmmakers today would even give so much as a nod to Christianity as having a part in the formation of our country.

History’s Shifting Winds

The answer is yes, but only barely. At one point the narrator acknowledges that William Bradford, governor of the Plymouth Colony, described the colonists’ purpose as “advancing the gospel of the kingdom of Christ.” That’s it. Admittedly, all I’ve seen is the first two-hour segment. But Kit (my wife) and I took notes on what we saw, and that lone mention marked the extent of any discussion of the Christian faith. We heard the word “religion” used, as in “freedom of religion.” We heard “moral compass.” We heard the phrase “religious dissidents with faith at the center of their lives.” We heard “seeking religious freedom.”

The terms “religion” and “faith” are broad-brush terms, sufficiently PC to be a catchall for any brand of “spirituality.” Is just any kind of spirituality sufficient for explaining the formation of the United States?

Here’s how the History Channel describes its series: “History takes a six-week look at how determination, hard work, and ingenuity made America.” Or, alternatively, “how self-determination and innovation made America.” So, still, I am wondering: was the “making of America” so purely secular?

For more on the program—including a link to the History Channel’s site—go here. And yes, the show does (otherwise) have many merits.

Comes now Mr. McNaughton, and his painting, which has drawn the praise (or ire) of millions.

What strikes this writer as remarkable about his story is not the fact that his painting drew angry responses. It was the fact that McNaughton has gotten so much flak for a message that, a few decades ago, would have hardly raised an eyebrow—at least from the standpoint of being objectionable. But we live in a world where, increasingly, the sacred is treated as profane, and the profane is treated as sacred. McNaughton’s case is just one example of a change that is affecting all of our society.

When the Mainstream Becomes the Fringe

His typical subject matter is material that used to be deemed conventional, heartlandish, Middle American, even ultra-traditional. When did the traditional become radical?

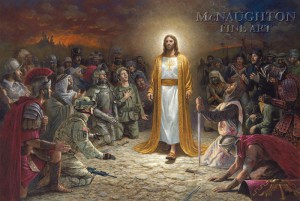

McNaughton’s supposedly “controversial” image portrays Jesus Christ holding a copy of the Constitution of the United States. Christ is surrounded by an array of figures both historical and symbolic. McNaughton’s unmistakable statement is that Christianity and the Bible were the wellspring that furnished the ideals of the Constitution.

He finished the painting in June 2009. For a few months it merely occupied space in his gallery. Then, in October, the artist and some of his associates created a video, accompanied with music and narration, telling the story of the creation of the artwork, and they posted the clip on YouTube.com. It went viral.

“At last count, the response was about 3 million hits,” McNaughton says. “And almost 2,500 comments on the site.”

Not all were favorable. In fact, a sizable amount of the feedback was hostile. “There are some people out there who just hate what this painting stands for,” the artist says.

To see the video, go here.

The essence of the painting, according to McNaughton, is that the Constitution is an inspired document. In defining the term “inspired,” McNaughton says he is not trying to say that Christ wrote the document. “And I’m not saying it is 100 percent perfect in every regard,” he says. “I’m saying the Founding Fathers were inspired. There had never been anything like it in the history of the world. Because of the Constitution, and the freedoms it has given Americans since its inception, mankind has had so many advances in science, medicine, and technology.”

[For an online, interactive display of the painting, one that allows viewers to mouse over each of the painted figures to reveal a capsule commentary of why that individual has a place in the work, visit the artist’s website at http://mcnaughtonart.com. There, on the landing page, you will see the image. Click on the image and you will be taken to the interactive version. – JFM]

The image has come up for ridicule in print, on television—in all forms of media. McNaughton said he’d heard that Bill Maher had poked fun at it, and that media on the East Coast was especially derisive. [Scroll down for continuation of article.]

One Nation Under God

McNaughton said he was not trying to suggest that each individual in the work was a professed Christian, or even a believer at all. The figure of Thomas Paine, for instance, is given a favorable treatment/portrayal in the presentation even though the man Thomas Paine did not profess Christianity. As McNaughton says, “I commented on my website that God uses good men and women to fulfill His purposes whether or not they are Christians.” What the artist hopes to oppose are not non-Christians per se, but rather “people who do things that are contrary to the Constitution and [contrary to] Judeo-Christian principles.” As he says, “They are the ones who will hurt us [as a nation].”

Huffington and Hate Mail

Much of the criticism directed at McNaughton’s image has come from viewers who decided, at little more than a glance, that this individual or that individual in the scene was not actually a Christian.

Not that the backlash hasn’t been strong.

“When the painting was first released, the Huffington Post, a very liberal news site, did a story on it, and from there it went instantly all over the country,” McNaughton said in a telephone conversation from his studio in Provo, Utah. “We were getting slammed. There were constant phone calls. People were yelling at me. I was getting hate mail. And I was wondering, ‘What have I done?’”

But it was only a matter of a few weeks before the situation flip-flopped, said McNaughton, 42. It was then that the sympathetic, favorable responses started trickling in, then pouring in.

And even some of the angry individuals were disposed to listen to McNaughton’s defense of his work.

“An atheist wrote me an 8-page letter telling me all the things I had done in the painting that was wrong. I replied to him, and a week later he wrote me a letter and apologized. He even showed me pictures of his kids.”

Dallan Wright, print production manager for FOV Editions, has worked with McNaughton for a number of years. He calls McNaughton a “family man” who “is very open and enjoyable to work with.” Wright says McNaughton is always professional, kind, and patient, possessing an even temperament.

An Artistic Transition

“When I first met him, there were not that many religious paintings that he had done. His [typical] scenes were peaceful, tranquil, but not overly religious in tone. A couple portraits of Christ. A few years ago he started painting more religious elements. But I guess more recently he has started to express in his paintings how he has always felt deep down. And he has been able to find a market that allows him to paint what he has always wanted to paint.”

As for the brouhaha over One Nation, Wright remarked, “I would say maybe a couple years ago this wouldn’t have been this big a deal, but it seems like the current climate is such that when the [political] right brings up the religious aspects of things, the left feels the pressure. And what we see is almost a kneejerk reaction. It’s easier, too, to focus on the visual than on something somebody has written.”

The more harsh reactions, Wright says, have been of such a nature that he would term them “nasty.”

“I’ve been surprised at the nastiness,” he says. “People would make fun of it. For people to actually have the energy to pick up the phone and call someone to try to chew them out about something… that shows that he definitely touched a nerve. I didn’t see any comments from anyone who [claimed to be] religious. But for those who did complain, [one could tell that] it just bothered them to think that their country might have been inspired by religious thinking.”

Through the Roof

The upshot of all the furor, Wright says, is that “sales went through the roof.” And for all the people who have been dismayed by the painting, there have been more who are inspired by it, he says.

Wright’s employer, which maintains a website at foveditions.com, handles such artists as Simon Winegar, Greg Olsen, Jim Norton (of the Cowboy Artists of America), and other notables.

Wright added: “I’d just like for people to know that Jon is sincere in what he does. He would do this regardless. He has a passion for it. He does not paint his images to get a reaction, either for good or bad. He is not focused on making a stir. He paints what he likes.”

Mike Singleton, owner of Sagebrush Fine Art (sagebrushfineart.com), publisher of many of McNaughton’s prints, calls the artist “one of the nicest people [he] has ever met.”

Sagebrush recently sold 50,000 reproductions of a single image—a nativity scene—by McNaughton.

“Jon recently burst onto the scene with a painting that one of my associates and he worked on together,” Singleton says. “Jason Bullard worked with Jon on Peace is Coming, which marked a turning point in Jon’s career.

“One Nation Under God is an image Jon painted—by himself—after Peace is Coming. One Nation… put Jon on the map. It was featured in the London Times. Presidents of big corporations have obtained copies. And he has received a number of commissions now, as a result of that image.”

McNaughton said the idea struck him as none ever had before.

The Genesis of the Idea

“I actually got the idea during the 2008 presidential campaign,” he says. “I had just found out that [U.S.] Senator [John] McCain was going to be the [Republican] nominee. I was really frustrated. I was sitting in my gallery, and I said a silent prayer to myself. I said, ‘God, what can I do? I am just an artist.’ In what was a powerful experience, I looked at my easel, and I saw in my easel this painting fully completed—saw it for about ten seconds.

“I sketched [from memory] as much of it as I could, and I used that as my guide as I prepared for the [actual] painting. It took about six months to paint it.

“Whether someone likes the painting or not, if it really gets you to think about your place in this country, and what you can do to contribute to this country in a positive way, then I think it was successful.”

The image is about more than just the idea that Christianity inspired the Constitution, McNaughton says. There are figures in the foreground and in the background. The background figures—depictions of individuals in the past—are separated from the foreground figures—which represent contemporary individuals or types—by a line of dust that seems to rise from the ground, separating the two groups. The figures in the background appear to be reaching out to, or imploring, the figures in the foreground, urging them to uphold the principles of the Constitution.

Among the figures in the foreground, those on the left side represent “strong Americans,” while those on the right represent types of people who are “not so good in supporting the values of the Constitution,” McNaughton says. “It’s not that I’m trying to condemn these [latter] individuals,” he says. “It’s just that they need to listen [to what they haven’t heeded].”

McNaughton says it is easy to tell, when someone approaches the image, which side they identify with. That’s the side that initially draws their vision.

To Each His Own

Moreover, “people who are politically savvy, whether they are religious or not, whether they are Democrats or Republicans, immediately know what the painting is about,” he says. “The only ones who see the painting and don’t understand it are people who do not know much about the country. Sometimes kids don’t get it. But among those who get it, they will either absolutely love it or absolutely hate it. It is really fascinating.”

Describing himself as—not surprisingly—a conservative, McNaughton says that he experienced pressure, during his academic career, to abandon his traditionalist/realist leanings and paint abstract forms. But he resisted that pressure, he says, and went his own way.

“If you were a rebel in the old days, you did modern art,” McNaughton says. “If you are a rebel today, you do traditional art.”

Much of his art education was, accordingly, self-administered. He “spent time in museums” studying the technique and style of the Old Masters, for one thing. He fell in love with the French Barbizon school of Impressionism, and with the work of Jean Baptiste Camille Corot in particular. But ultimately he fashioned a style of his own. His early work was mainly landscape subjects. Now that he has switched more to the human form, the detail work has become more demanding and time-consuming for him.

“I have to ‘tighten up’ quite a bit with religious paintings,” he says. “I like strong conceptual paintings that make people think.”

Make people think, yes. But McNaughton is not shy about directing their thoughts. With One Nation, he tried to load the image “with as much straightforward information as I wanted it to have,” he says. “Everyone who sees it knows exactly how I feel about things.”

Some have suggested to him that he didn’t leave enough room for people to interpret matters for themselves.

“But I didn’t want to leave material for interpretation,” he says emphatically.

And is it hard to see why? Like the Constitution itself, some truths ought to be held as self-evident.

For more on this topic (specifically, my defense of McNaughton ideals against someone else’s published challenge to him), go here.

To go to this site’s main (home) page, click here.

To return to the menu page for the e-newsletter (Something Solid, Issue 2), click here.

COPYRIGHT 2010 JESSE MULLINS