“What we choose to see, hear, and read matters greatly. People need good stories just as they need home-cooked meals, clean water, spiritual peace, and love. A good story is part of that process. It affirms divine order in the universe and justice in human affairs—and it makes people better than they were before they read it.”

—John R. Erickson, from Story Craft

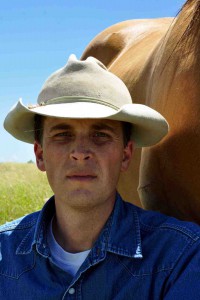

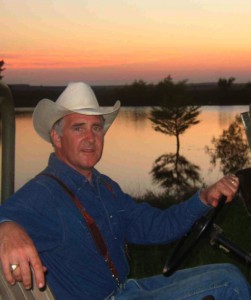

The creative force behind Hank the Cowdog is more than just a cowboy, rancher, author, publisher, and family man. He is a thinker and a force for good in a world that could use so much more of what he represents.

“An American treasure.” That’s who John R. Erickson is to many who are in-the-know about this Texas-based cowboy-turned-rancher, the creator of the hugely successful humorous book series known as “Hank the Cowdog.”

More than 7.5 million copies of Hank the Cowdog books and audios have entertained buyers appreciative of the Texas author’s unique storytelling talents and his priceless sense of humor.

In the past two decades Erickson has been courted by such network heavyweights as Disney and Nickelodeon for animation rights, but thus far he has held out, mainly because he has been unwilling to compromise the values of his franchise.

That story—of a heartland author holding out for wholesomeness and virtue in an age when standards elsewhere are in swift decline—is a stand-up-and-cheer event. If the literary world had more John Ericksons, the reading public would not just be blessed with more quality reading material. No, the public would be a better public, period.

I am convinced that if more Christian authors and thinkers were to heed Erickson’s examples and his advice, art itself would be elevated. And Christianity could approach its former prominence in society-at-large—a development that could only lead to greater public enlightenment, productivity, and prosperity—to say nothing of salvation.

Those are huge claims, and I know that John Erickson would never make them for himself.

And I am not saying that any artist by himself or herself could ever, will ever, exert such profound effects on the wider world.

But what I am saying is that Christian influence and uplift, in Western society, has always preceded societal, scientific, educational, and economic gains.

This position has never been plainer to me than after reading Erickson’s new book Story Craft. Not because Erickson gave any history lessons. But because Erickson explains how art and literature are meant to “nourish the human spirit, not poison it.”

He applies an analogy of a compost heap:

People who tend compost heaps are fanatical about what goes into them. It must be organic material, never garbage that might include solvents, plastic, paper with ink or dye, or inorganic substances that might be harmful.

“What you put into your compost heap is what you eat. This is chemistry at its most basic level, also known as nutrition. If you give your compost heap garbage, it gives you garbage back.

“The same principle applies to the creative process. I never know exactly what will come out of my mental/spiritual compost heap. The characters, dialogue, and plot lines that end up in my stories bear some resemblance to the experiences I’ve had, yet they’ve been transformed in mysterious ways into something else. But the important thing is that they don’t become toxic.” (Story Craft, p. 56)

Elsewhere in his book, Erickson writes that he knows of no profession outside the arts that permits a practitioner to invent his craft as he goes along.

“It happens every day in modern America, where the artistic elite, representing what I call ‘Uppercase Art,’ has turned its back on four thousand years of tradecraft and moral tradition. Art today has become what an ‘Artist’ does, and if that happens to be loathsome, too bad.” (p. 79)

And there’s also this: “’Uppercase Art’ in modern America has become a synonym for arrogance, irresponsibility, vulgarity, disrespect, and wild suicidal self-indulgence.” (p. 81)

Against this enveloping tide—what some, myself included, would classify as Postmodernist secular humanism—Erickson makes his case for Christian literature, and by Christian literature he does not necessarily mean a literature that merely spouts Christian/Biblical doctrine and/or principles. He takes a broader view that considers also the influence of a Christian worldview upon the writer’s own personality and outlook, and the creative products that arise from such nourishment.

“I think we can establish a kind of statistical grid that offers some clues about the broad characteristics of Christian literature—and notice that it has nothing to do with the repetition of “faith” words, such as God, Jesus, Bible, or Gospel. Christian literature as a total body of work is more likely to be structured than chaotic, more likely to be harmonic than dissonant. It is more likely to find justice, beauty, hope, and resolution than their opposites.” (p. 63)

For more comments from Erickson in these veins, click here.

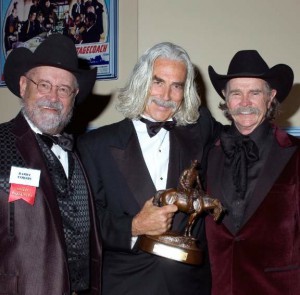

I was alerted to Story Craft, which I consider a landmark book, a few months ago when I opened a copy of the Christian Chronicle to see it reviewed in their pages. (Click here for review.) I knew Erickson from my years as editor-in-chief of American Cowboy magazine. In fact, in 2006, a two-part article authored for us by John won the Western Heritage Award for Best Magazine Article—a national competition. In April 2007 that honor was conferred during a black-tie event attended by 1,200 patrons of the sponsoring National Cowboy Museum. So, yes, I knew John Erickson, for he had been responsible for the highest honor our magazine had ever received.

But I had not been aware that John had ever written anything in this vein—what might be called philosophy or ideology. So I immediately obtained a copy and began reading what I believe is a book that ought to matter to more than just writers—to Christians and concerned citizens everywhere.

And I’m not the only one.

“I wish Story Craft would be read by more people,” said Nathan Dahlstrom, a friend of Erickson’s and the photographer who shot most of the on-location (ranch) photos displayed in this article (and in related webpages on this site). “I tried to talk someone else [a more mainstream publishing house] into publishing it. [Erickson published it under his own publishing imprint, Maverick Books.] There is a lot of important material in there. It needs to be read by people in the media. It needs to be read by students.”

Dahlstrom voiced concern that, because the print run was modest and the book is not being marketed and distributed by a major publishing entity, it will not get the exposure it merits. “I wish I had a way to get more people to read that book,” he said.

So do I. Hence this coverage. And I’ll have more to say, further below, about Story Craft. But there is more to John R. Erickson than his latest book. There is also the phenomenon that is Hank the Cowdog.

Not familiar with Hank the Cowdog? If you are a parent with kids aged, oh, anywhere from early teens on down into the elementary years, chances are your child has at least heard of Hank, if not enjoyed him personally. Hank has a high saturation level in American schools and juvenile reading circles.

It’s more than just books. Erickson, who has a gift for doing voices and considerable musical talent (singing and playing), began from the outset to record the books as audio offerings. The books themselves are written for reading aloud, and they make great experiences for sharing—whether among friends or within families.

Erickson’s first Hank stories were written as humor for grownup audiences, having found earliest publication in The Cattleman magazine. It was only later that he packaged them for juvenile audiences.

“I had never intended the stories to be for children,” Erickson writes in Story Craft, “and it’s a good thing I didn’t. If I had set out to write children’s stories, I would have assumed that children were not capable of appreciating my best licks as a writer. I would have written down to the audience.”

That assessment is echoed by someone who was one of my most valued freelance contributors when I was editor-in-chief at American Cowboy. Connie Hubbard heard I was writing on John, and she had this to say:

“When my 3rd-generation-rancher father had his penultimate stroke, he lost his ability to focus on a book. Since he could no longer ride or drive at that point, we used to read to him. His favorites were Hank the Cowdog books and he’d laugh until the tears rolled, infecting all of us with whoops of mirth. The story in which Hank fell for the [attractive young female] coyote, Missy Coyote, was a hoot. When Hank began to see her looking just a little like her mother as time wore on it had us all doubled over in laughter. Those books are NOT just for kids.

“He [Erickson] made my father’s final few months a lot more fun than they otherwise may have been… and we appreciated him more than he’ll ever know.”

For those not among the Hank cognoscenti, this cowdog regards himself as Head of Ranch Security. Because of that self-appointed role, and because he is a dog, Hank makes everything in his world his business. He is suspicious, smug, excitable, easily ruffled, reactionary, and pompous. And, being a dog, he has a short attention span.

Hank sees all varieties of monster. The airplanes that occasionally pass overhead—“silver monster birds,” to Hank—are stealthy threats to ranch security and they do not escape his vigilance.

He’s also naïve, gullible, and an easy mark for such archrivals as Pete the Barn Cat. By the end of each story, though, Hank generally shows his best qualities and comes off rather endearing and even a bit admirable.

Sometimes enlisting the assistance of the affable Drover, whom Hank inwardly, and sometimes outwardly, regards as “the mentally pathetic mutt,” or “the runt,” (as in, “I stared at the runt”), he solves mysteries—some imagined, some real—around the ranch. (For a taste of Erickson’s winning way with a running gag – and he is a master of it – see this bit from the Hank book shown at right.)

Sometimes enlisting the assistance of the affable Drover, whom Hank inwardly, and sometimes outwardly, regards as “the mentally pathetic mutt,” or “the runt,” (as in, “I stared at the runt”), he solves mysteries—some imagined, some real—around the ranch. (For a taste of Erickson’s winning way with a running gag – and he is a master of it – see this bit from the Hank book shown at right.)

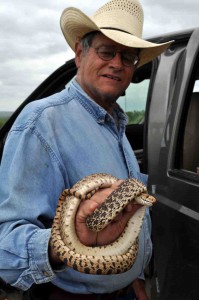

I’d been to the Ericksons’ own ranch, called the M-Cross, outside Perryton, in the northern part of the Panhandle, some dozen or more years ago, and I have interviewed John on more than one occasion, besides having bought and published articles of his. I was a fan of his nonfiction prose even before I was acquainted with his Hank material. (Cowboy poet Baxter Black once said of his friend: “If West Texas Cowboy had been a book in the Old Testament, John Erickson would have been the author.”) For a side jaunt into the ranching dimension of Erickson’s ranching life, click here.

So, recently, when I interviewed him for this piece, it was a matter of catching up on changes in his life.

“Well, I think the way my life changed in the last few years is that I am spending more time with Christian groups, home-school groups, churches, and Christian schools,” Erickson said. “I still do a lot of ‘Hank programs’ in the public schools. That’s rewarding—I enjoy it.”

Erickson said that there have always been those people around who have “seen things in the Hank stories” that could only be called spiritual. This despite the fact that the Hank books make little mention of Christianity or the Bible or church-going, other than the fact that the ranch family does attend church.

“Those [spiritual elements] are things I’ve always considered important. They are things that have been there—I don’t know if ‘by design’ is the right way to say it, but there by instinct,” he said. “And I’ve always gone to trouble to protect those things from being chewed up, or corrupted, by popular culture.”

That is a large part of the message of Story Craft, Erickson said.

“For years I was just making my living as an author/entertainer/public speaker and I always had certain standards. But I wasn’t trying to preach. Yet it was through the teachers and librarians who invited me into schools I began to realize there was a spiritual element in those stories that I had put there and protected. I had not put that much thought into it. I was just pulling my plow… trying to pay off a ranch.”

It was friends and acquaintances of Erickson’s who were members of the church of Christ (Dahlstrom, Chuck Milner, and Sandra Morrow among them) who were among the first to say to Erickson (himself of the Methodist persuasion) that there was a spiritual element to his writing that clearly displayed his reverence for God, whether God was mentioned in his writing or not.

Sandra Morrow, librarian at the Austin, Texas-based Brentwood Christian School, created the Lamplighter Awards (given continuously since their inception in 1992) to “encourage elementary and junior high students to read wholesome and uplifting books by providing lists each year of the best literature.” She became acquainted with Erickson when he became a Lamplighter winner in 2004 for his youth-market novel Moonshiner’s Gold.

Morrow noted that Erickson had always worked within the public schools to promote his Hank the Cowdog series. “These stories were enormously popular and it seemed as though Mr. Erickson would continue to add to that series and be perfectly happy for the rest of his life,” she said. “Then, for some reason even he may not have known at the time, he wrote Moonshiner’s Gold. Mr. Erickson was totally unaware that this title was getting a great deal of attention from students within the National Christian School Association. The book was so well received that the students voted it the 2004 Lamplighter Award. He was very moved by that and he realized that his Christian worldview had been a part of his writing all along. For the first time he saw that his was a God-given talent and he felt compelled to record his literary journey in Story Craft and its follow-up, Small-Town Author: How Hank the Cowdog Began in the American Heartland. (The book is not yet scheduled for publication.)

“I was privileged to get to read this latter title as a manuscript. I was struck by how driven Mr. Erickson was to write day in and day out for years, with very little return. He was unwavering in his pursuit of his literary dream and all the while worked as a cowboy to provide for his growing family. It seemed as though getting published was out of his grasp and still he would not give up. God certainly did not give up on him.”

Milner, a friend of Erickson’s, is another individual who read and critiqued Story Craft (“I thought it was pretty awesome”) in manuscript form. He also has worked alongside Erickson in the saddle, and he knows Erickson’s main constituency (school-age kids) from having done in-school programs himself.

“I’ve been an entertainer—I was an artist-in-residence for 8 years—and I do the education programs for the Working Ranch Cowboys Association,” Milner said. “We go to every fourth grade in Amarillo. I’ve probably done over four or five hundred programs. And I’ve never been to a school anywhere in the United States where the kids didn’t know Hank the Cowdog.”

For Erickson, there came another step in his journey towards deeper self-awareness when, about three years ago, he was invited to Virginia, to the campus of Patrick Henry College, to speak to students there.

“I was so impressed with that college,” Erickson said. “They are training kids to go into professions where their Christian worldview can be put into practice and they can change the world a little bit at a time. When I was up there I was surprised at how respectful they were of me, because I am not an evangelist. But they were very respectful. A lot of those kids were raised on Hank books. They wanted to know what it was I had put into the stories.”

It was just another nudge from his appreciative readers, wanting to know what that “special something” was in the Hank stories. So Erickson—himself not fully satisfied about the nature of that element—set out to define it for himself, and for others.

“My first audience [for the message that would become Story Craft] was going to be the kids at Patrick Henry,” he said. “So I spent 18 months on it. It was the most difficult book I ever wrote. That’s because I was trying to put into words things I had been doing instinctively. The Hank books are deeply rooted in a Christian worldview, and that is one of the reasons why teachers and librarians can recommend them to kids. They know that there is not going to be any objectionable material in them.

“So that [realization] is where Story Craft came from,” he said.

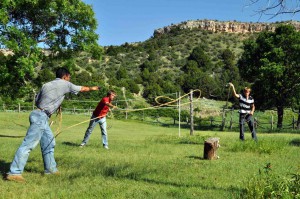

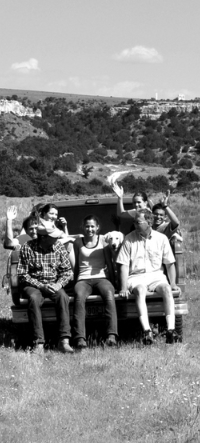

Meanwhile, Erickson decided to invite students from Patrick Henry to a weeklong creative seminar conducted on the grounds of his M-Cross Ranch. Students who have come to the ranch (he has held the seminar two years running) have lived on site for the week, and taken part in ranch activities, as well as their studies. Erickson has developed his own lesson plans for the events. This year students from some Texas colleges were included along with the Patrick Henry contingent.

“I want to share with these kids my experience as a writer,” Erickson said. “My experience is not backed up by a lifetime of reading every book ever written. I don’t have a doctorate in anything. No teaching credentials. But I do have some insights that I have gained in more than 40 years of being a writer, and I am willing to share that with the kids. And they seem to think I have something worth teaching them.”

In this past spring’s event, the author kicked things off by launching into the first three chapters of Genesis.

“That is where it is all laid out for us, and the most important concept in those three chapters, is that human beings are not absurd little robots on an absurd rock circling the sun in an impersonal universe,” he said. “We contain a divine spark that was given us by our Creator and one of the ways we thank God for this is by producing beautiful art, so for me it is a Christian calling.”

Erickson cited Marshall McLuhan’s famous remark that “the medium is the message,” but gave it his own spin:

“If the medium is chaotic, then it reflects a chaotic view of the universe, which is not Biblical. Our founding document is the Book of Genesis and it tells where we came from and it tells us that it was an act of creation. It was willed by the Creator. One of the first things God did was to separate the darkness from the light. And the firmament (water) from the earth. And he created an orderly universe and that is fundamental to a Christian worldview.

“We are a special act of creation,” he added. “We were given dominion over the earth. As it says in the Psalms, ‘created a little lower than the angels.’ And so to me Christian art should reflect the order in the pattern of God’s design. When we find art that is disjointed and jagged and absurd and hopeless, it means that it is not Christian. It means that it is bad art.”

Erickson said he is much influenced by Gene Edward Veith, and he underscored Veith’s remarks about our “vocations” as Christians (God at Work: Your Christian Vocation in All of Life, Crossway Books, 2002).

“He [Veith] resurrected the Reformation concept of vocation, which is that everyone, regardless of how big or small, has a cluster of vocations, and it is our job as Christians to do a thorough job with our vocations. I have a vocation to be a husband to my wife. That is a godly task. A Biblical pursuit. Ordained by God in the Book of Genesis.

“So that is probably my most important vocation. And then, I have a vocation as a father to my children. And one as a rancher—a steward to my land. That land is God’s gift to me. And as that is God’s gift, it is up to me to protect this land, not overuse it, not rape it.

“I am also steward to my livestock—I consider them part of my godly vocation. And then, too, as a writer. And part of that vocation is to find order in chaos… to find beauty in ugliness, to find God’s design in our world. Now, that sounds very presumptuous for a guy who writes funny stories about a dog who isn’t very smart. But that happens to be my vocation. And it has been a very good vehicle for doing God’s work.”

His books do God’s work “in ways that are very mysterious [to him],” Erickson said. As an example, he cited the fact (also discussed in Story Craft) that teachers and mothers of autistic and dyslexic kids have come to him thanking him for what he has done for their students/children.

Some letters he has received have “given [him] a jolt,” he wrote in Story Craft.

“After I had gotten three letters… in the space of a month, I wrote back to one of those mothers and asked, ‘What is your child finding in my stories? I know nothing about autism.’

“She pointed out that autistic children fight a constant battle against mental chaos. They crave structure and order. My stories are orderly and structured. They all have 12 chapters and the same cast of characters. They all begin with the same sentence: ‘It’s me again, Hank the Cowdog,’ and most end with ‘Case closed.’

“They all have happy endings and in every story, justice is affirmed. When Hank makes a dumb mistake, he pays for it. When he makes a good decision, he enjoys a moment of triumph—before he blunders into another mistake.

“Those letters didn’t come from literary critics. They came from mothers and teachers who were involved every day in the process of nurturing—giving life. And from them I learned that my business is not books. It’s nourishment.” (p. 105)

It’s not a meaningless world, Erickson said. “And yet dilettantes can play with chaos, and meaningless existence, and it is just a toy for them. But if you are autistic and fighting against mental chaos, it is not a game. People in the entertainment business who contribute to that disorder—to me, that is obscene.”

Britt Hancock, a church-planting missionary and a friend of Erickson’s, is an advocate for the author’s work. “Hank the Cowdog has been a part of our family’s entertainment for years,” Hancock said.

Describing himself as an “independent” as regards his denominational affiliation, Hancock said he was raised in the Assembly of God fellowship and spent some of his formative Christian years at the non-denominational New Life Church in Colorado Springs, Colo.

Today, he lives with his family in the mountains of northern Puebla (Puebla is a state in Mexico), where his missionary efforts are an outreach to the indigenous populations there, including the descendants of the Aztecs. He works with other language groups there as well. Says Hancock: “We have congregations in about 48 villages.”

So how did Hancock come in contact with John R. Erickson?

“On my oldest daughter’s 18th birthday, she wanted her mother to read to us from a Hank the Cowdog book. We’d been doing that for years. I grew up on a farm in rural Alabama, and we had always had dogs, and [for a storyteller] to humanize dogs, well, it was hilarious.”

So the mother [Britt’s wife, Audrey] read to the family. Later, touched by the sentiment of the moment, the feeling of family closeness that comes from sharing a storytelling tradition, Britt felt he just had to convey those feelings – somewhere. So….

“I jumped on the Hank the Cowdog website [www.hankthecowdog.com] because I had noticed [from an earlier visit] that you could email Hank. So I emailed Hank and told him thank you for providing such great family entertainment with such strong values. I told him it was my daughter’s 18th birthday and that we were missionaries in Mexico.”

About 3-4 days later, Hancock received a personal email from Erickson.

“We started up a friendship from there,” Hancock says. “And we were invited to an event where they were going to dedicate a monument to Hank. From that, things have kinda progressed. Now we go out to the ranch. That’s a cool thing. I am blessed by our relationship. He is a neat man.

“His [Erickson’s] ‘grid’ that he thinks from, and from which he views society and analyzes the moral content around him, is the fiber and stability of our nation,” Hancock said. “It’s like what we had with the World War II generation. Their perspective about life anchored us—and we are losing those people. I think it is essential to have an understanding of the principles that underpin our society. Part of that is a direct connection to the ground—to working with your hands. And John, though he is intellectual, is someone who works with the ground. That connection is what shapes his views about life and [provides the] angles by which he sees everything. That is what gives it its strength and validity. He is the whole package.”

Jeryl Hoover is another individual who was spent considerable time around the author. And like the others quoted here, he has read Story Craft.

“It’s a great book,” said Hoover, a former Baptist minister who is currently a professional actor and musician. At one time Hoover used to do musical programs in the schools along with Erickson. He confirms that “there is a lot of affection for John and his books out there.”

“I’ve known John about 12 years and I always felt he was really guarded about how he felt about his product and his abilities and what he was trying to accomplish with his work,” he added. “I’ve never thought he really liked talking about himself. What Story Craft did for me is to let me inside his heart. It is a really good explanation of who John Erickson is and why he does what he does. It gave me a great deal of respect for him as a writer and a person.”

As Erickson remarked (earlier), one of the recent changes in his life has been his involvement with the home-school movement. A key figure in his life, in this connection, is George Clay, whom Erickson has known for a number of years.

Clay, who resides in Wichita Falls, Texas, said he met John at a home school conference in Houston in 2004 when the author came there as a keynote speaker/performer.

“It was the first home school conference he’d ever done, and I took him and his wife and wife’s mother out that night, just to get to know them,” Clay said. “We hit it off immediately. I feel like I have known John my whole life.”

Erickson, meanwhile, recounted some eye-opening experiences following that conference.

“On the trip back to the Panhandle, my wife and I noticed the startling contrast between the young people we saw in the airports and those we’d met at the convention,” he wrote in Story Craft.

“The homeschooled children at the convention were serene, clear-eyed, polite, clean, at peace. They seemed to know who they were, and their sense of identity began in the knowledge that they are part of God’s creation. From that everything else flowed naturally. Their home-based education was a process of learning about the roles we are meant to play in a plan that was here before we were born, a plan we don’t have to re-invent every day.

“In the airports we saw many children of pop culture: young people with empty eyes and graceless gestures; girls who showed no hint of modesty or virtue, and boys, flabby and tattooed, staring at nothing and bobbing their heads in time to the clattering sounds piped into their heads through headphones.

“Their appearance suggested a generation whose only purpose is to consume and feel good, and then, like summer moths, to die. Their faces revealed the tragedy of lives without structure, including the wonder of God’s plan.” (p. 107)

Clay confirmed those sentiments. “That was one of the things he was so amazed at,” Clay said. But there was a good side to it all. “With the children and the families he was meeting at the homeschoolers convention—with those kids looking him in the eye—it was like he had hope again for this generation.”

Erickson was a “tremendous hit” at the convention. There was a packed house for the first (Friday) night of the event, when he performed. Erickson consented to do a second evening, and they had another 800 in attendance for that one.

“There was a standing [unwritten] rule that you don’t invite the same speaker back for the following year’s conference,” said Clay, who, in his working life, is president of High Plains Health Providers (caregivers for developmentally challenged adults). “But he has been there every year since. He continues to be a hit and everyone loves him.”

Clay said that John’s wife Kris travels often with her husband, and at a conference such as the Houston one, Kris would go on stage with her mandolin and John with his banjo and, with hardly a word of introduction, would launch into two or three songs from the Hank stories.

“A lot of people in attendance may have read the songs in the books but they have not heard them put to music,” Clay said. “So, for the first time, they hear the voices of John and Kris, and those two have a beautiful duet.”

After that beginning, John engages in banter with the audience.

“Then he’ll do something real simple. He’ll open up a book and he’ll read five, six, or seven pages. He’ll give the context of it all. He might do six or seven different voices. John can change his voice any way he wants to… and he does.

“And that,” Clay said, “is what we call a ‘Hank talk.’”

Clay has been to the ranch on multiple occasions. He said that Erickson “reads voraciously” and that the author “gets up early every morning and writes for hours.”

“And there are times when, if you ask him, ‘What did you write about today?’ he might say that it was nothing special—that it was the events of the last day or maybe something he read about recently.”

Clay has been on the ranch for the seminar events. “Every waking minute, John and Kris are serving these kids and giving them—some of them—the best week of their life. I’ve heard a couple of the kids actually say that. They said, ‘This was the best week of my life.’ And if you saw the way that John and Kris kind of ‘co-minister’ to these kids, well, it is kind of amazing.”

More than one source for this article remarked that Erickson has been known to pull an amusing trick or two.

Clay said that John warns visitors to the ranch to be sure to roll up their car or truck windows when they park there. The reason is simple. Pete the cat is notorious for entering through open vehicle windows and urinating in one of the seats.

“Well, for some reason [here Clay chuckled at the memory] John forgot to tell me. I slept in the bunkhouse that night.”

The next morning George and John had someplace they needed to go, and George volunteered his vehicle. A window had been down.

“We climbed in,” George said. “As soon as we were seated, John had this grin on his face. I didn’t know at first what was funny. He said, ‘Don’t you smell that?’ At first, I couldn’t tell what it was. But he could. Fred the cat had paid a visit.

“Kris acted furious with him,” Clay added. “She said, ‘John, why didn’t you tell him?’ He said, ‘I just didn’t think of it.’ She said, “John Erickson, you forgot on purpose!’

Not that it doesn’t work both ways. On another occasion, when Erickson was traveling and Clay was going to see him off to the airport, Clay was left in temporary care of Erickson’s luggage. “So I put about 30 pounds of rocks in it,” Clay said. “I was thinking to myself that he would lift it, and realize it was weighted down, and he would then get rid of the rocks. But he didn’t figure it out. And they charged him $100 to check that bag. So….[he laughed]… we go back and forth.”

Chuck Milner knows that side of Erickson too. “You can imagine that he is full of pranks,” he said.

But there’s more to the author than his humor.

[Story continues below photo…]

“I can’t emphasize enough how universal he is to the children of America,” Milner said. “I am proud that he has given them something wholesome. My thing is teaching people, and no matter where we go, I can always interject a mention of Hank the Cowdog, and kids’ eyes will just light up. ‘I know Hank!’ they’ll say. ‘I know Drover!’”

His own kids quote Erickson, Milner said. “When certain things happen, they have a saying to go with it. We’ll have a cow get down [take sick], and my daughter will say, ‘Well, you know what John says. “Not sick enough to die, but too sick to get well.”’ So, yes, they’ve always got a John Erickson saying. And sometimes one to give me a hard time with!”

Milner said he feels blessed to know his friend.

“He has brought something decent into the world,” Milner said. “And the gift of laughter—what a blessing that is.

“It’s almost like a dream. I almost want to pinch myself. I live about 80 miles from him, and I can call him my friend.

“I’ll tell you what I think,” he said in summation. “He’s an American treasure.”

For additional insights/commentary about John Erickson from some of the same sources quoted in this article, click here.

For a sampling of John Erickson as a commentator on the national scene, see this brief commentary on World magazine’s site.

To visit the official Hank the Cowdog website, click here.

Copyright 2010 Jesse Mullins