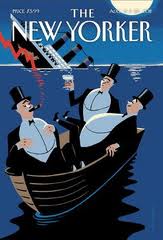

If Newsweek thought they had set the bar impossibly high for outré mockery of presidential candidate Michele Bachmann, they can think again. The once-redoubtable New Yorker, formerly a paragon of impartiality and objectivity, trumped Newsweek with its own patently partisan takedown of the suddenly prominent Republican.

Both magazines discharged their broadsides in mid-August. We’ll never know how many thousand outtakes and trashbin rejects Newsweek sifted to find its cover shot (see photo). But you’ll recall the image, certainly, with its Onion-like exaggeration. It’s a practice that is simply the flip side of the Obama adulation rampant in the 2008 election, when major media saturated the newsstand with heroically framed halo shots of their newest messiah on their covers, backed up by valentines printed inside. Get used to it. We’re all back in junior high and this is now the way of the world.

Newsweek’s cover swipe at Bachmann, with its vacant-eyed, dazed-looking subject staring out over a headline panning her as “The Queen of Rage,” was barely in the public eye before the New Yorker struck with a hit piece of its own (“Leap of Faith,” New Yorker, Aug. 15-22).

In a campaign trail boobytrap seemingly aimed more at influencing an election outcome than serving a paying, trusting readership, the New Yorker opted for the ill-concealed-disdain route, painting Bachmann and her husband as a couple of campaigning Midwestern rubes so dense they could not properly read the cues of their own handlers, much less the barely masked scorn lurking amongst the accompanying press.

But if truly “exposing” Bachmann was the magazine’s goal, it was a job for the old New Yorker, not this New Yorker. This New Yorker is a descendant who is too knowing—and being too knowing, is accordingly too naive. The sheer incomprehension put on display—that is, the incomprehension of the New Yorker as confronted with the everywhere-on-display phenomenon that is main street American evangelicalism—is breathtaking.

With reporter Ryan Lizza cozily embedded on a bus tour, a fifth columnist among the invited press corps, the task of lifting the lid off of Bachmann’s Christian convictions began. And while we could dissect Rizza’s too-predictable conclusions, such analysis is hardly lacking. Bachmann has tens of millions of staunch supporters, and hundreds of media outlets that are only too ready to air her side of a controversy. The backlash has already begun.

But that backlash has been in support of Bachmann, not the other individuals who were impugned by the New Yorker. Foremost of these was the late Francis Schaeffer, who comes up for criticism as some kind of far-out religious wacko.

But Schaeffer is himself too well known, and too highly revered, by too many erudite, well-regarded, highly placed Christians, for his reputation to suffer too much by these knocks.

The person who was most unjustly maligned, and who has received the least vindication, in this affair is author Nancy Pearcey, a figure who is less well known than Bachmann or Schaeffer and yet who is introduced to us as “one of the leading proponents of Schaeffer’s version of Dominionism.” Upon learning what had been said about her in the article, Pearcey wrote a piece that appeared on humanevents.com, under the headline: “Dangerous Influences: The New Yorker, Michele Bachmann, and Me.” The Aug. 12 piece included the following remark:

“Lizza labeled the two of us Dominionists,” Pearcey wrote. “Dozens of liberal websites have picked up the story and repeated the charge. I had to Google the term to discover whether there really is such a group. Yes, there is a little-known group of Christians who claim the term, though they are typically called Reconstructionists. Apparently it was sociologist Sara Diamond who expanded Dominionism into a general term of abuse, based on a passage in Genesis where God tells humans to exercise ‘dominion’ over the earth.”

It didn’t require Pearcey’s input for Christian readers to seize upon the flimsiness of Lizza’s premise, with its undertones of impending Christian takeover.

For Something Solid’s exclusive Q&A with Nancy Pearcey, go here.

Joe Carter, at First Things, had nothing but withering scorn for the Dominionism silliness: “There is no ‘school of thought’ known as ‘Dominionism,’” he wrote. “The term was coined in the 1980s by (author Sara) Diamond and is never used outside liberal blogs and websites. No reputable scholars use the term for it is a meaningless neologism that Diamond concocted for her dissertation.”

In that Aug. 10 piece, which firstthings.com called “A Journalism Lesson for the New Yorker,” Carter also had this to say:

“The excruciatingly long (8,300 word) feature is intended to be a magnum opus of revelations about presidential candidate Michele Bachmann. And indeed it does break new ground. Did you know that in a speech about her family moving to Iowa in 1857 she confused a plague of grasshoppers with a plague of locusts? Yes, you and I know that locusts are grasshoppers; Lizza and the New Yorker fact checkers probably do too. But if you put the words in scare quotes and imply that they are different you can give the impression that Bachmann somehow made a mistake.”

Carter gives Lizza too much credit. Here’s how Lizza springs his trap. He has already documented that Bachmann said her forebears survived “a plague of locusts.” But by consulting the actual text of the family history that Bachmann was referencing, Lizza is able to inform us that what the family really encountered, in pioneer-era South Dakota, was “the awful winter and the flooding and the drought and what the text calls ‘grasshoppers.’” There. Bachmann is exposed as either ignorant or as careless with facts. Except that, no, it’s the New Yorker that is ignorant or careless with facts.

There’s too much of that sort of Bachmann-peccadillo-hunting for us to bother exposing.

Meanwhile, though, to pull off his bigger sophistry, Lizza had to take a couple of the most mainline of Christian thinkers [Schaeffer and Pearcey] and convince his readers that they are a pair of beyond-the-pale radicals, hatching a sort of fundamentalist anarchy soon to rise into view.

To do this, what Lizza needs is readers’ buy-in on a line like this: “He [Schaeffer] was a major contributor to the school of thought now known as Dominionism.”

So that’s exactly what he serves up. I could serve up a line of my own. I could say, “Schaeffer was a major contributor to the school of thought known as Christianity.”

Now which statement of these two would the reader be most willing to bet his life upon?

But instead of conceding the obvious to Schaeffer and Pearcey, Lizza floats his conspiratorial-sounding theory, and we are off and running. From there, it’s just a game of three-degrees-of-separation till we have Schaeffer linking arms with the likes of R.J. Rushdoony.

It’s all an old, old story. Or “an old paranoia,” as Ross Douthat described it in his landmark essay of 2006 that should have driven the stake through the heart of this oft-resurrected theme once and for all. In that rollicking, fun-filled article (“Theocracy, Theocracy, Theocracy,” First Things, Aug/Sept 2006) that put the Theocracy exposers themselves to the chase, Ross Douthat scattered the brood so decisively that they have hardly dared rear their heads until now.

But things die down. People forget. And half a dozen years later we see that the Theocracy zaniness has been morphed into Dominionism.

Richard John Newhaus called Douthat’s article “delightfully devastating” and some have credited the piece for winning Douthat his current post as a columnist for the New York Times. Whatever one’s opinion, it is clear that the lunacy that Douthat debunked in “Theocracy” is the menace that now alarms the editorial offices of the New Yorker.

As Douthat showed us, giving names to the Christian menace is part of the whole rabble-rousing thrust of the Theocracy-busting machine.

“There isn’t perfect agreement on what to call the religious radicals in question,” he wrote. “Everyone employs theocrat, but Kingdom Coming also proposes Christian nationalist, while The Baptizing of America favors the clunky Christocrat. Others have suggested Christianist, the better to link religious conservatives to Osama bin Laden.”

Douthat quotes Rabbi James Rudin so as to show us “what America will look like if the theocrats get their way”:

“’All government employees—federal, state and local—would be required to participate in weekly Bible classes in the workplace, as well as compulsory daily prayer sessions,’ as would employees of any company or institution receiving federal funds. There would be a national ID card, identifying everyone by their religious beliefs, or lack thereof—and ‘such cards would provide Christocrats with preferential treatment in many areas of life, including home ownership, student loans, employment and education.’ Non-Christian faiths would be tolerated, ‘but younger members. . . would be strongly encouraged to formally convert to the dominant evangelical Christianity.’ Gay sex would be prosecuted, and ‘known homosexuals and lesbians would have to successfully undergo government-sponsored reeducation sessions if they applied for any public-sector jobs.’ Political dissent would be squashed, religious censors would keep watch over the popular culture, and ‘the mainstream press and the electronic media would be beaten into submission.’”

But we’ve covered enough. All that really remains are some questions.

How could the New Yorker have been so tone deaf to the common vernacular and commonplace beliefs of the nation’s evangelicals? After all, we are talking about roughly 30 percent of the nation. How is it that, in “Leap of Faith,” the magazine could have been so myopic as to not see its own imbalance and offhandedness so blatantly on display?

It’s not that observers do not expect the New Yorker to have an agenda or to have an axe to grind. Of course we do. It’s a left-leaning, partisan magazine.

It’s just that we are used to seeing major media be more refined and subtle in its political axe-grinding. We are used to seeing a veneer of objectivity, a modicum of even-handedness.

If the New Yorker wants to recover some of the effectiveness it used to have, it should relearn how to produce a personality piece that at least gives the outward appearance of being something other than a literary letterbomb.

Till they (and other major media) do, we’re all back in junior high. Who would have thought that sophistication would become the hallmark of the hinterlands, while cultural illiteracy grows ever more apparent in the centers of population and learning?

As John R. Erickson, a Texas-based author and a friend of Pearcey’s, has observed:

“We’re not provincial. They are. We read their magazines, attend their movies, and listen to their news broadcasts. We know a lot about them. They know nothing about us.”

That’s becoming more true all the time. Does it presage a power shift? If it does, it could be the bellwether of a refreshing breeze across the land.

Jesse Mullins is publisher and editor of Something Solid, a website dedicated to matters of God, family, and country. His bio can be accessed here.

NOTE: Lizza and radio show host Terry Gross discussed the Christian beliefs of Michele Bachmann on the Aug. 9 installment of National Public Radio’s program “Fresh Air.” By clicking here, you can listen to that program.

For the most in-depth personality profile of Nancy Pearcey to be found online (and one that has been widely shared via social media), click here.

For editor Jesse Mullins’ in-depth Q-and-A with Nancy Pearcey conducted two weeks after the New Yorker article broke, see this page.